Research

Urban Ecology & Evolution

Ecological consequences of urbanization a legume-rhizobia mutualism

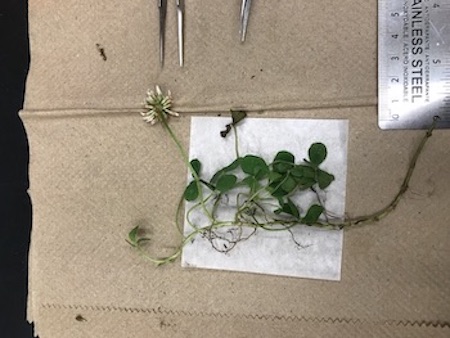

Mutualisms between plants and microbes are critical for community development and ecosystem structure and function. One example of a plant-microbial mutualism is between legumes and rhizobia, whereby legumes provides photosynthate and nodule habitat to rhizobia in return for nitrogen (N) fixed by the rhizobia. For my thesis research, I am using the mutualism between white clover (Trifolium repens) and its primary rhizobial symbiont, Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar trifolii, to study how urbanization affects the ecology and evolution of mutualisms. Urban environments are frequently associated with increased N deposition, acting as both a source and sink for N. As N is the key nutrient in the exchange between white clover and rhizobium, increased N availability should disrupt the interaction in this focal mutualism. Here, I was interested in asking: (1) Does rhizobia nodulation vary along an urbanization gradient? (2) How does the source of plant nitrogen change along the urbanization gradient? And (3) how do urban landscape features influence the interactions and feedbacks between soil N, plant N, and rhizobia nodulation?

From this project, there were three main conclusions: (1) Urbanization decreased investment in the mutualism, (2) white clover acquired N from different sources along the gradient, and (3) there were direct and indirect effects of urbanization on soil nitrogen and white clover-rhizobium interactions. If you would like to read more, please see the published article.

Diversity and assembly of the microbiome of a leguminous plant along an urbanization gradient

Urbanization can drive spatial variation in soil chemistry and nutrients, which can affect the assembly and composition of soil microbial communities. As plant microbiome assembly is ultimately determined by the microbes present in the local soil community, changes to soil microbial composition can affect plant microbiome assembly and function. Notwithstanding growing research into microbiomes, there is limited evidence demonstrating how microbiome assembly and diversity varies within and among natural populations of the same host. This project will begin to fill the gap by quantifying the urban-driven changes to microbiome structure. For my thesis research, I sampled white clover, rhizobia, and soil along an urbanization gradient in the Greater Toronto Area, ON, Canada to (1) evaluate how microbiome composition varies among soil and root compartments and (2) identify the underlying drivers of microbiome assembly and composition. I have completed the bioinformatic pipeline and data analyses, and will be presenting the results in a preprint shortly. Stay tuned!

Mosaic of local adaptation between white clover and rhizobia along an urbanization gradient

Bacteria and fungi comprising the microbiome are important for plant community assembly, physiology, and response to stressors. As bacteria and fungi can have different functional roles relative to rhizobia, the function of the root microbiome is a multifaceted and emergent property of the ecological roles played by rhizobia, bacteria, and fungi. Alterations to microbiome structure could therefore strongly impact plant communities and associated ecosystem functions. Using a manipulative experimental, I am asking (1) are white clover and rhizobia locally adapted? (2) Does N addition mediate any effects of local adaptation? and (3) how does the degree of local adaptation vary with urbanization?

For this experiment, I am using 30 populations of white clover from an urbanization gradient in the Greater Toronto Area, ON, Canada. Each population is crossed with three microbiome (local, nonloca-rural, and nonlocal-urban) and two nitrogen (10 mM KNO3, ambient N) treatments, with 6 replicates for each treatment combination (1080 total plants). At the end of the experiment, I measured fitness estimates for both the plant and rhizobia.

Our results show a spatial mosaic of local adaptation, with stronger local adaptation for rhizobia than white clover. While nitrogen addition (N) strongly influenced plant biomass and nodule density, it did not consistently mediate patterns of local adaptation. The strength of local adaptation was positively related between white clover and rhizobia under N addition, suggesting that soil N mediates coadaptation between white clover and rhizobia. Local adaptation was not influenced by urbanization, indicating that while urbanization does influence the ecology of plant-microbe interactions, it does not disrupt local adaptation and coevolution. If you would like to read more, the preprint is available on bioRxiv and the article is in press at Journal of Ecology.

(Meta)community Ecology

Community assembly and diversity

A fundamental question in community ecology is: what drives community assembly? This is not an easy question to answer, as communities are the result of the dynamic interplay between local and regional factors. I am currently working with my partner and fellow researcher Kelly Murray-Stoker to address this question. We are using publicly-available data collected by the United States Environmental Protection Agency to evaluate metacommunity structure and the environmental, landscape, and network variables that best predict realized assemblages at the macroecological scale. We have found that communities can display consistent metacommunity typologies despite varying drivers of assembly. Future work will go beyond the elements of metacommunity structure and the paradigm of metacommunity typology frameworks to (1) test and compare models of community assembly (2) understand community assembly across taxonomic groups and freshwater ecosystem types at the macroecological scale.

I am also interested in patterns and drivers of diversity, taxonomic, functional, and phylogenetic. Working with collaborators on open datasets, I want to quantify functional trait diversity of river and stream communities and to identify predictors of trait diversity across spatial scales. Additionally, I want to examine how communities and associated functional diversity respond to disturbance and environmental change at local, regional, and macroecological scales.

Niches and community (dis)equilibrium

Understanding and predicting community responses to environmental change are essential components for applying community ecology to global change problems. Evaluating how community composition relates to the niches of organisms comprising the community is one way to measure the effect of environmental filtering and niche matching towards community equilibrium. Through the framework of disequilibrium theory or DisEQ, we asked: Q1 = How do environmental filtering and habitat matching vary across ecoregions? Q2 = How does functional trait diversity vary across ecoregions? Q3 = Which functional traits are linked to environmental filtering and habitat matching? Q4 = What are the environmental predictors of functional trait abundance?

Our study demonstrates spatial patterns of environmental filtering and habitat matching in communities across ecoregions at the macroecological scale, with functional traits providing a critical link between disequilibrium metrics and the environment. We published this project in the Journal of Biogeography, and I hope to explore the implications and applications of this work in the future.